On the over-use of concept-checking questions: part 1

There aren’t many things that I think should be comprehensively banned from EFL classrooms, but the use of closed CCQs (Concept-Checking Questions) for items of vocabulary is one! For those of you unfamiliar with CCQs, they seem to have come into the ELT mainstream via International House and the very early teacher training courses offered there, and have gone on to become part of what is now widely considered to be CELTA orthodoxy. The basic idea is that simply explaining what something means is insufficient and therefore teachers need to ask their students questions to check whether or not they’ve actually grasped the ‘concepts’ that have been laid out for them. CCQs tend to be closed yes / no questions and just to be clear, I’m not opposed to their use in all circumstances.

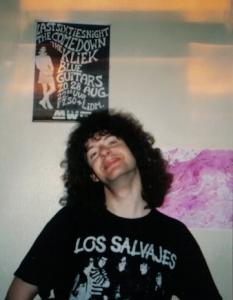

They make perfect sense on those (hopefully fairly rare) occasions that you’re dealing with a grammar structure that students may not have encountered before, and are doing your presentation, with the setting up of a context, and the model sentences that end up on the board. Imagine, if you will, that I’d asked a student to draw a quick cartoon of me now and had then drawn a little picture of me thirty years ago – hair much longer, cigarette in hand, sunglasses on, bottle of vodka on the go – and had asked the class what differences they could see, which either resulted in a student noting that I used to have long hair or me having to say it myself. I’d probably end up with sentences like these on the board:

I used to have really long hair.

I used to smoke a lot more.

I used to drink a lot more.

I used to go out five nights a week.

I used to play in a band.

Now, I’d hope the context made things clear, but just to check I might then ask “So do I have long hair now?” And get the answer “No!” “And in the past? When I was younger?” “Yes!” Job done. CCQs work well here because the form is clear from the examples and the underlying meaning of the structure can easily be checked with these two short yes / no questions.

Of course, none of this means I’d expect students to have now magically ‘got’ this structure or that they’d realistically start using it at every possible opportunity henceforth. They may start using it correctly in one or two sentences, possibly to say things that are true about themselves and that they’d been helped to say during the class. However, I’ve been at the job long enough to recognise that broader accurate usage will take time and will depend of further exposure and noticing, L1 influence, conscious recycling of things via teacher talking time, reading and listening texts, and so on.

However, when we come to vocabulary, CCQs become something of a curse. A typical example of their misuse can be illustrated by asking you to picture the following scene. It’s an Intermediate-level class and the students are reading a text. An arm goes up and someone asks what the word abandoned means. Wary of being seen as too ‘teacher-centred’ or of telling students what they could potentially tell him / her, and keen to encourage learners to deduce new items from context, the teacher launches into the CCQs. “Well, is this building abandoned?” One or two rather bemused-looking students manage a “No”. “But what about at night? Is it abandoned then?”. It’s at this point the class grinds to some kind of halt as students avoid eye contact, mutter shared translations between themselves or sneak a peek at a dictionary under the table.

Now this may sound like an extreme example, but I’ve seen similar occurrences time and time again. The first and most obvious thing to say here is that there’s little point trying to check whether or not students understand something if they’ve just asked you what it means! Even if you do want to use CCQs, there needs to have first been a ‘concept’ that is then checked. This means the first step is for the teacher to look at context in which the item in question appeared and explain the meaning from there. This might mean saying something like “An abandoned house is a house that’s been left empty and is no longer used. The owners have just left it – they’ve abandoned it – and it’s now slowly falling to pieces.”

Once you’ve done this, the kind of closed CCQs above become, at best, redundant and at worst, ridiculous. If students have understood your explanation, they’ll struggle to grasp why you’re asking if a building in which they’re currently studying is abandoned – even at night! The answer is so obviously no that it’s patronising to even bother asking. It requires almost nothing of the class and it adds almost nothing to students’ ability to use the word in any kind of meaningful context. Meanwhile, of course, any students who didn’t get your initial explanation, for whatever reason, are still none the wiser and will almost inevitably now resort to the aforementioned survival techniques of avoidance, translation or dictionary use!

When I was thinking about where I wanted to go with this blog post, I Googled CCQs to see what advice is out there on the web for novice teachers still getting to grips with everyday classroom procedures. One of the first sites I came across recommends using CCQs after you’ve defined a word such as banana. As it notes, “you may have talked about fruits, shapes, peel, the favourite food of chimpanzees, etc. but how do you know the students have understood? They may have completely misunderstood the meaning of banana and confused it with an apple.” It then goes on to suggest that if you have just taught the word banana, you can ask the following questions: Is a banana red? Are bananas hard or soft? Are bananas eaten by monkeys or tigers?

My immediate thought on reading this was that if you can’t clearly clarify to a low-level group what a banana is you probably shouldn’t be teaching. My next thought was that if you had managed to successfully convey the meaning, asking if bananas were red and eaten by tigers is such a singularly odd thing to do that teachers shouldn’t be surprised to find students simply gawping in bemusement. It’s yet another example of how singularly twisted dialogue in a second language can become!

Now, none of this is to say that there aren’t useful questions that can be asked in each of these situations. There obviously are. It’s just that they are most definitely not CCQs. In the second part of this post next week, I’ll look at some saner alternatives.

[…] On the over-use of concept-checking questions: part 1 | Lexical Lab. There aren’t many things that I think should be comprehensively banned from EFL classrooms, but the use of closed CCQs (Concept-Checking Questions) for items of vocabulary is one! For those of you unfamiliar with CCQs, they seem to have come into the ELT mainstream via International House and the very early teacher training courses offered there, and have gone on to become part of what is now widely considered to be CELTA orthodoxy. The basic idea is that simply explaining what something means is insufficient and therefore teachers need to ask their students questions to check whether or not they’ve actually grasped the ‘concepts’ that have been laid out for them. […]

Thanks for your interesting post. It’s very easy to diss initial teacher training programmes like CELTA, I know. I think you have set up the very simple closed (Y/N) type of concept-checking questions as a kind of straw man. Here are some points n favour of questioning learners about meaning:

First, CCQs are comprehensible input. “Nuff said.

Secondly, they are a chance for output, especially when they are in the form of open-ended/read/referential questions, which I find are more challenging and interesting at higher levels. (I can send examples on request, but I think you are about to post something about these real questions next week?)

Thirdly, CCQs are a chance for the teacher and students to negotiate meaning. In ISP Nation’s Learning Vocabulary In Another Language, there is a section entitled, What Learning Conditions Help Vocabulary Learning? Nation writes on p.104 that, “vocabulary items that are negotiated are more likely to be learned that are not negotiated” and – very importantly for CCQs – “observing others negotiating is just as effective as doing he negotiation.” (Nation, 2013)

Fourthly, asking questions keeps the learners engaged in the clarification stage of lessons.

Finally, it’s a chance for teachers to check efficiently which students have and have not understood unfamiliar language.

Hi Neil –

Thanks for your thoughtful (and detailed!) response. I’ll try to answer the points you’ve made as best as I can over the next few days, so bear with me if I don’t cover everything in one go.

Firstly, I have to say, this post wasn’t intended as a dig at CELTA courses . . . though if the use of CCQs as part of vocabulary teaching is current CELTA orthodoxy, then of course, it IS critical of that aspect of them.

Next, the idea that CCQs somehow serve as ‘comprehensible input’ is a perversion of the original concept. Krashen’s notion involved what he termed i+1, where i is the current level of the students, so by definition a question in language they understand about an item they maybe don’t quite yet cannot be that. Comprehensible input is far more usually what we call reading or listening texts slightly above current level, where not all the grammatical structures may have necessariyl been covered in details yet.

Finally, for tonight, the idea that they offer some space for output: by definition, CCQs are closed questions, and as such, the output they offer the chance for are yes / no responses, or other one-word responses. AS you’ll have seen from today’s post, I think there are other kinds of questions that extend students far more when we’re dealing with new lexis and that provide far more scope for student output than the severely limited CCQs.

More soon.

Hugh

Hi Hugh

Thanks for your thoughtful reply.

You say that, “…by definition, CCQs are closed questions.” This is begging the question. I encourage my students to use open, referential and actually real questions to check students’ understanding, restricting the Y/N ones to where they are checking genuinely unfamiliar language.

Regarding comprehensible input I take your point about i+1 as being the point where new language can be acquired, according to SK. It remains true that CCQs are useful (and comprehensible) input – which stimulates students to respond. Just like real questions – because many of them are.

Straw men!

Look forward to reading your second post, which I’m sure deals with the other kinds of questions that we’ve both referred to here.

Hi again Neil –

Hope you’ll have had time by now to read the second post of questions we ask about lexis we deal with. I suspect we may well agree about the best kinds of questions to ask more than we initially seemed to, especially if you’re including more open types of questions in your definition of CCQs!

Not sure, though, how my attack on the narrow Y/N CCQs can be accused of setting up a straw man, given how prevalent their use still is – as can be seen from the strident defence some folk felt compelled to make of them on social media, etc.

Hi Hugh

I’ve read your interesting second post. I agree with most of what you’ve said – on the value of open/referential questions, in particular, and that there is probably no need for immediate productive use of lexis.

You mention that you might possibly ask what else might be described as abandoned, and ask why a building (or a car or a child) might be abandoned. I’m not sure what precludes these from being CCQs exactly. I certainly include these more interesting questions in the repertoire of concept-checking techniques I offer to candidates. They are CCQs in my book by virtue of the answers’ yielding evidence that a student has understood the word or structure in question. As you point out, they may be used to prompt more output, but this is beside the point here.

You mention that CCQs may seem redundant when used with the example, “I was really disappointed when I found out I hadn’t got the job.” But in this example, you might equally well feel depressed – or even relieved. Your choices as a teacher would then be (a) some elaborated input, along the lines recommended by Mike Long i.e. “redundant” explanation – or (b) redundant-seeming CCQs. My question is simply, why rule one useful technique as out of bounds? Is it purely to make a point?

It seems to me that all question types are worthy of continued inclusion on training courses. One 75-minute session in a four week course, together with some comments on lessons, is surely justified.

Hi Neil –

Thanks for the further comments.

I think we’ve basically reached a point of agreement on most things other than the fact that you see the kinds of questions I’ve outlined in my second post on this subject as still somehow falling under the bracket of ‘CCQs’ – and I don’t! I see them as being something that have a far less catchy title – QUESTIONS ABOUT LANGUAGE THAT GENERATE LANGUAGE – and believe they do far more than simply ‘check concepts’.

With the questions about DISAPPOINTED, I’d suggest that DEPRESSED doesn’t work here as DEPRESSED is a longer-term state of mind, rather than a fairly momentary condition. I’d also suggest you want to avoid going near another kind of synonym here unless forced to. I still fail to see what’s wrong with a T explaining that if you feel disappointed when something you thought was going to be good turns out not to be – and then just asking ANY OTHER TIMES WHEN YOU MIGHT FEEL DISAPPOINTED?

That seems to be to be the easiest and most direct way of covering meaning, checking students understand / learn other contexts of use and giving students the chance to add their own ideas to extra emerging examples. It also doesn’t seem (to me, at any rate) to involve any “redundant explanation”.

Traditional yes / no CCQs are fine on training courses – so long as they’re restricted to grammar presentation slots where they do a clear and useful job. Elsewhere, trainees need to be taught to think about why certain questions work better with certain items than others do!

You seem to have deleted my latest reply? Here are some CCQs for ferry which illustrate what I’m trying to say. They are wide-ranging. https://eflrecipes.com/2014/06/11/concept-checking/

I too agree with most of what you say. The more open kinds of questions I also mentioned in my original reply here, before I’d seen your second post. I’ve always advocated them – because they check the concept AND generate further language use.

I agree with your explanation of DISAPPOINTED and with the open question you follow it with, but fail to see the problem with the closed questions which are certainly “elaborated input” (Long) as well as an example of NEGOTIATING MEANING (see my first reply here) and as such may benefit the slower students who didn’t catch on immediately to your first explanation! This is what Nation’s research found.

My simple point is this: why rant and rail against a useful technique, which might as well be part of the repertoire of question types a teacher can use?

I agree with you about not using near synonyms to explain lexis too. Incidentally, this is another reason why the closed CCQs you so despise can be so useful against a watertight context to kind of “hone” the nuances of meaning, and keep students involved as you do so.

I have to say, Neil, I think you’re stretching the boundaries of ELT terminology rather spectacularly here. You must know that when Long talked about elaborated input, he wasn’t talking about CCQs for vocabulary – and as far as I’m aware, Nation, in his copious studies on vocabulary teaching and learning, hasn’t actually written about this particular issue either. Oh, and NEGOTIATING MEANING was never meant to describe the process of a teacher asking closed CCQs to a class either, but hey!

I get that you’re a fan of them and don’t want – or don’t feel the need – to reassess their value in your courses, but not sure you need to come up with a slightly twisted view of the literature to support those emotions.

From here, there seems little point repeating the issues I have with CCQs, as I’ve laid those out in detail across both posts.

Of course Long wasn’t talking about CCQs – but nevertheless, they can be a kind of elaborated input. Nation wasn’t talking about CCQs, but nevertheless these are a case of NEGOTIATING MEANING *par excellence* – and led by a skilled negotiator. (See my first post here.)

You’ve inadvertently reminded me of this, Neil:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

Excellent! You and me both, then.

Think we may have gotten as far as we’re going on this area, then. Thanks for the discussion, though.

Yes. I look forward to the next one – perhaps in person at Brighton.

Here are some CCQs for the word “ferry” which illustrate what I’m trying to say. They are wide-ranging. https://eflrecipes.com/2014…

Interesting post and comments, When I teach I do a lot of what Hugh suggests, but I often find myself falling back on Y/N questions to check that the collocations/ extensions that the students have given are correct. For example, in a recent class I taught ‘to go on about’ and when I asked students what other things their parents go on about I followed up with ‘Do they say it once or many times?’, ‘Do you like to hear this?’ to make sure their suggestions are correct.

I agree with this approach. It’s good to mix the closed and open questions.

Or after watching boring lessons you could ask your trainees: do I slash my wrists now or later?

A question best asked internally as opposed to verbalised out loud, in my experience. 🙂

Hi Matt –

Thanks for your thoughts and comments.

For me, once you’ve ‘taught’ GO ON ABOUT – by which I assume means EXPLAINED, and then given an example showing how it might also grammar (e.g. HE’S ALWAYS GOING ON ABOUT HOW CLEVER HIS KIDS ARE!)I’d see the simple question

Hi Hugh,

On our CELTA courses CCQs are used as just one of a list of about a dozen ways of checking meaning, and effective ones are very helpful to students of all ages, as long as the teachers/trainees are aware of their limitations as well as when to use them. Your argument seems to be based largely on ineffectively written or used CCQs, which is a bit unfair to the poor, innocent CCQ in itself. It’s clear that not only trainees have a problem putting them together or using them effectively. The banana example would be clearly ridiculous to our trainees for starters, but even your questions about ‘used to’ would be considered context checking, not concept checking, since they’re not generic enough to ensure the student has understood the concept of the structure, but just the individual context.