Something better change: taking a stand against gender bias in ELT

Earlier this year I spoke at the very first International Language Symposium in Brno, the second-biggest city in the Czech Republic. Prior to the conference itself, I’d agreed with the organisers that I’d be doing a plenary and a workshop, saw that several people I knew from the ELT world would also be there and then thought little else about it until a few days before I was due to leave, when I ran through my sessions and made sure I was ready to roll.

Once there, I was asked if I’d take part in a panel discussion that would bring the first day – the day I gave my plenary on – to a close. I agreed and as the day drew to a close, I found myself sitting on a stage next to Jeremy Harmer and Philip Kerr, both of whom I must confess to knowing and liking, Huw Jarvis, and Stephen Krashen, who I’d obviously read a great deal by before, and had seen speak a few times, but didn’t know personally. The session was based on questions from the audience and got quite heated, particularly after I took offence at Krashen’s rigid certainty and insistence that only extensive reading was worth doing, as his research proved other forms of learning to be less effective. Yet another aging guru who has long since lost any interest in the efforts of everyday classroom practitioners, I fumed, and the heat that the disagreement generated seemed to both entertain and amuse a tired crowd, if subsequent feedback was anything to go by.

That night, before crashing out, I made the fatal mistake of having a quick look at Twitter and found that a positive tweet Marek Kiczkowiak had sent out had been picked up on by Nicola Prentis, who’d responded with an angry, sneering “The old white man line-up strikes again. What are your excuses this time?”

My first thought was “Old? OLD! How very dare you! I’m at least eight or nine years younger than Philip, twenty years younger than Jeremy and half a lifetime younger than Stephen Krashen!” and I did what I have been conditioned to do when under attack – strike back. “Less of the old!” I quipped back, followed by “First kid in my family ever to go to uni. Dad a second-hand car dealer. I’ve fought for every ‘privilege’ I’ve ever managed to get.” And that was just the start of it. It got out of control quite quickly, but thankfully some of the calmer voices (female, as it happens) in the discussion pulled things back from the brink and amidst the flurry of 140-character ravings (mostly mine), one particular tweet really hit me, and subsequently stuck in my mind.

“Privilege is intersectional”, it read, “and you can be privileged in some regards and lack privilege in others. White male panels are a systemic problem.”

A few weeks after that, I watched the wonderful Raoul Peck documentary I Am Not Your Negro, based loosely on some of James Baldwin’s later autobiographical writing, but essentially an overview of the crucial importance of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. to the fight for black rights in the USA, a fight which, as recent events in Charlottesville have made disturbingly clear, is anything but over. I reflected on the fact that the fiery, radical, uncompromising Malcolm X was clearly the necessary counterbalance to the more placatory, peaceful Martin Luther King, and on the fact that agitation and activism cannot – and should not – always tailor their message and tone to suit the ears of those they are railing against.

As some of you may know, I’ve been a long-time supporter of the work that Marek (aforementioned) does with his TEFL Equity Advocates site, where he pushes for native and non-native teacher equality, and I found Silvana Richardson’s 2016 IATEFL talk on this subject devastatingly convincing. By now, and after – it must be added – long conversations with my co-author and partner in crime Andrew Walkley, who was insistent from the start that the current status quo is simply wrong and cannot be allowed to continue – I’d started to feel that it was untenable to back one attempt to combat a clear discriminatory practice in ELT and yet remain silent on another.

The tipping point for me was a book I’ve just finished reading: The Descent of Man by (occasional) transvestite working-class artist Grayson Perry. In the age of Donald Trump, it’s not hard to argue that masculinity all too often turns toxic, and Perry nails many of the dangers connected to the way our society constructs what it means to be male. He also notes that:

“Our classic Default Man is rarely under existential threat; consequently, his identity has tended to remain unexamined. He ambles along blithely, never having to stand up for his rights or defend his homeland. What millennia of male power has done is to make a society where we all grow up accepting that a system grossly biased in favour of Default Man is natural, normal and common sense, when it is anything but.”

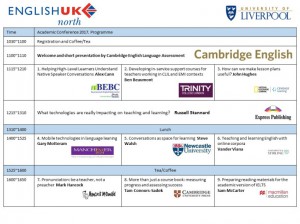

Facts are facts and ELT around the world is a female-dominated profession, yet it remains the case that male-only panels, such as the one we started this post off with, are still conceptualised and allowed to come into existence. Conferences such as the English UK North one earlier this summer, which caused outrage online for featuring not a single female speaker in its initial lineup, publish their programmes with nary a thought for the message this sends.

Much has already been done to raise awareness of these issues, via organisations like The Fair List, which lobbies for better gender balance at ELT events. But still, something more is desperately needed. And whilst it clearly needs angry voices shouting from the sidelines, it also needs men with at least some degree of power to recognise this and do more than simply play gesture politics or write defensive blog posts.

Here’s what Andrew and I have decided to do – and we recognise it’s still only drops in the ocean, but hope it’s at least a start and that it puts pressure on other men to maybe think about doing the same:

(1) Refuse to take part in male-only panel discussions.

In an ideal world, we’re told before a conference if we’re expected to be on a panel. At this point, we can ask if a gender balance has been considered and explain our red line re. participation. This in itself will hopefully change things, but if by some chance we end up being asked on the day or turn up to find we’re still sitting next to only men, we’ll simply politely refuse to take part and suggest our place go to a female speaker instead. if and when this occurs, you’ll know as we will tweet about it.

(2) Write to conference organisers in advance enquiring whether they’ve factored gender and ‘non-native’ balance into their programmes.

It’s easy to send a generic email that reads something like “I’m very excited to be speaking at your forthcoming conference and am looking forward to seeing other talks by speakers who I hope will reflect the diversity of the ELT profession. Towards these ends, can I just check that there will be a suitably mixed range of speakers and that you have sufficient numbers of both female and non-native speakers, thus avoiding the ‘old white man’ trap it’s all too easy to fall into?”

We could all do it every time we get invited to talk anywhere.

I’m sure there are other things we could also do, of course, but this is a start.

We welcome any other suggestions on what could happen next to bring about a change.

To find out more about the work Nicola Prentis has been doing to promote equality for women in ELT, see this excellent database of female ELT speakers.

Leave a Reply