Oct 28, 2017

Hugh Dellar

Complicating the coursebook debate: part 4

In this post, I’m going to look at how I would use the material from Outcomes Intermediate that I mentioned in my previous post. As I would generally tend to do, I am going to look at the material in the order it is laid out in the book, but let me reiterate that this does not mean this is the only possible order to follow, or that I believe there will be immediate student uptake of all the language looked at in each activity, or that I think language will be acquired in the same sequence as it is presented in.

1 Speaking

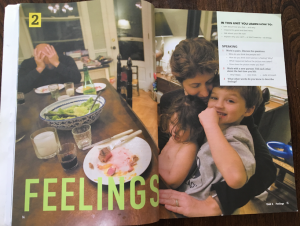

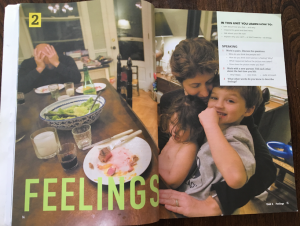

So at the start of this particular lesson, there’s a photo of a family at the end of a dinner. It’s a rather ambiguous scene that students discuss. During this discussion, students generally may well try to use copula verbs such as look and seem (which is the grammar point on the next page) and they might say things like ‘He looks like depressed’ or ‘He look too much’. There are choices to be made at this point. If students do make mistakes with the copula verbs, the teacher could choose to:

1 Speaking

So at the start of this particular lesson, there’s a photo of a family at the end of a dinner. It’s a rather ambiguous scene that students discuss. During this discussion, students generally may well try to use copula verbs such as look and seem (which is the grammar point on the next page) and they might say things like ‘He looks like depressed’ or ‘He look too much’. There are choices to be made at this point. If students do make mistakes with the copula verbs, the teacher could choose to:

2 Vocabulary (feelings)

The coursebook sequence of tasks now moves on to vocabulary. Usually, I would tell students they are going to learn more language about feelings and then set them the task to ‘guess’ (there are options given) the meaning of the words in bold from the context. The idea is to help develop students’ ability to guess unknown vocabulary in context (I’ll talk more about this in next post, by the way). While the focus of the material may be taken as the list of the adjectives in bold here, my aim as a teacher and writer is to look at language beyond these adjectives. I would expect students to know the meaning of some of the adjectives already, and maybe even all of them if they have studied them at home before the start of the unit, but of course this is different to being able to use the words in conversation or in a text.

When I am going through the answers to the first part, I usually ask questions akin to those in the next part of the vocabulary section (see below), and may also draw attention to chunks, patterns and grammar. For example, this is one example from the exercise:

We left at six in the morning and didn’t get back till midnight. I was exhausted.

From this, I might explore aspects of the pattern here by telling students about a night out. I might say – and maybe write on the board – I went out at 10 at night and didn’t get back home till 7 in the morning. I might then perhaps elicit ideas from students about exhausting days or journeys they have had using the pattern.

Another example is I was pleasantly surprised by the film. I didn’t expect it to be so good. Here, I might ask students about the opposite of pleasantly surprised (= disappointed) and give students prompts to complete such as: I was pleasantly surprised by the weather. I expected it … or I was a bit disappointed by the hotel. I …. .

I don’t assume this new language will necessarily be learned at this stage, but I believe that the noticing might help students pick up the pattern didn’t …. till / until …. or provoke errors with (and subsequent noticing of) patterns around the word expect. And in noticing this here, they may notice it when they read and talk outside the class, which, over time, may transfer to uptake.

I might also ask about grammar. For instance, I might ask ‘Why does it say she was furious about the mess they had made – why use the past perfect there?’ I can ask this here because we looked at past perfect in the previous unit, and so I know they probably haven’t mastered it then and need to revisit it (as they will do in various tasks that follow and over the rest of the course).

The second task for the vocabulary here is a number of ‘divergent’ concept checking questions of the type discussed in this post. They explore usage of the words (because words are not just about meaning). While this isn’t a natural conversation, it is a meaning-focused task in the way a quick crossword is and some of what students try to say in response to these questions will result in errors and opportunities for acquisition – though (at the risk of repeating myself) I do not assume that any language I subsequently correct / teach here will be acquired at that point.

At the end of the vocabulary section, I would normally add another task which is not in the book, where students talk about a time they experienced one or more of these feelings and / or I would ask them to talk about the photos along the top of the page. In fact, this task was originally there in the final draft of the book, but was cut due to lack of space on the page. I do this partly to give students the opportunity to practise (or proceduralise, if you prefer that term) some language they have learned, but I also accept that the choice of language is up to the students and they may use language other than that which has been ‘taught’. In giving feedback on this task, I do much the same as before. I notice some gaps in knowledge or where communication breakdowns have happened, and I try to help students overcome them. Some of that help may mean referring back to something which was ‘taught’ before, sometimes it will be something new.

Sometimes students try to say language which I know is included in a later exercise in the lesson or even in a later unit (as I have written and used the book, I often remember these things!), so I might make a particular point of teaching that language here (because I know students need repeated exposure to language in different contexts over time). I also try to keep some kind of record of language that has come up through tasks and has been highlighted so I can revise it another day or recycle it in my teacher talk. I might write it down or take a photo of the boardwork.

Presumably, as I can’t listen to all conversations at the same time, there will also be other moments where students have to get round difficulties they have, which may also lead to acquisition (or not!).

2 Vocabulary (feelings)

The coursebook sequence of tasks now moves on to vocabulary. Usually, I would tell students they are going to learn more language about feelings and then set them the task to ‘guess’ (there are options given) the meaning of the words in bold from the context. The idea is to help develop students’ ability to guess unknown vocabulary in context (I’ll talk more about this in next post, by the way). While the focus of the material may be taken as the list of the adjectives in bold here, my aim as a teacher and writer is to look at language beyond these adjectives. I would expect students to know the meaning of some of the adjectives already, and maybe even all of them if they have studied them at home before the start of the unit, but of course this is different to being able to use the words in conversation or in a text.

When I am going through the answers to the first part, I usually ask questions akin to those in the next part of the vocabulary section (see below), and may also draw attention to chunks, patterns and grammar. For example, this is one example from the exercise:

We left at six in the morning and didn’t get back till midnight. I was exhausted.

From this, I might explore aspects of the pattern here by telling students about a night out. I might say – and maybe write on the board – I went out at 10 at night and didn’t get back home till 7 in the morning. I might then perhaps elicit ideas from students about exhausting days or journeys they have had using the pattern.

Another example is I was pleasantly surprised by the film. I didn’t expect it to be so good. Here, I might ask students about the opposite of pleasantly surprised (= disappointed) and give students prompts to complete such as: I was pleasantly surprised by the weather. I expected it … or I was a bit disappointed by the hotel. I …. .

I don’t assume this new language will necessarily be learned at this stage, but I believe that the noticing might help students pick up the pattern didn’t …. till / until …. or provoke errors with (and subsequent noticing of) patterns around the word expect. And in noticing this here, they may notice it when they read and talk outside the class, which, over time, may transfer to uptake.

I might also ask about grammar. For instance, I might ask ‘Why does it say she was furious about the mess they had made – why use the past perfect there?’ I can ask this here because we looked at past perfect in the previous unit, and so I know they probably haven’t mastered it then and need to revisit it (as they will do in various tasks that follow and over the rest of the course).

The second task for the vocabulary here is a number of ‘divergent’ concept checking questions of the type discussed in this post. They explore usage of the words (because words are not just about meaning). While this isn’t a natural conversation, it is a meaning-focused task in the way a quick crossword is and some of what students try to say in response to these questions will result in errors and opportunities for acquisition – though (at the risk of repeating myself) I do not assume that any language I subsequently correct / teach here will be acquired at that point.

At the end of the vocabulary section, I would normally add another task which is not in the book, where students talk about a time they experienced one or more of these feelings and / or I would ask them to talk about the photos along the top of the page. In fact, this task was originally there in the final draft of the book, but was cut due to lack of space on the page. I do this partly to give students the opportunity to practise (or proceduralise, if you prefer that term) some language they have learned, but I also accept that the choice of language is up to the students and they may use language other than that which has been ‘taught’. In giving feedback on this task, I do much the same as before. I notice some gaps in knowledge or where communication breakdowns have happened, and I try to help students overcome them. Some of that help may mean referring back to something which was ‘taught’ before, sometimes it will be something new.

Sometimes students try to say language which I know is included in a later exercise in the lesson or even in a later unit (as I have written and used the book, I often remember these things!), so I might make a particular point of teaching that language here (because I know students need repeated exposure to language in different contexts over time). I also try to keep some kind of record of language that has come up through tasks and has been highlighted so I can revise it another day or recycle it in my teacher talk. I might write it down or take a photo of the boardwork.

Presumably, as I can’t listen to all conversations at the same time, there will also be other moments where students have to get round difficulties they have, which may also lead to acquisition (or not!).

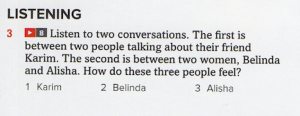

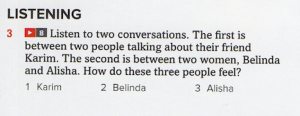

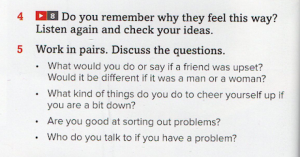

3 Listening

The coursebook sequence now moves on to a listening task. In this particular case, the listening is a kind of model for a conversation the students will do at the end of the lesson (and that we think they might hear or take part in outside the class). As I mentioned before, while it does contain items of the grammar, it is the conversation and its naturalness that is the starting point, with the grammar being selected afterwards. I think the conversation here does sound natural (in the way a drama script might) despite the fact that it isn’t actually authentic speech with all its pauses and overlaps and fillers, etc. I hope to discuss this more in a post on materials banks at a later date.

The listening also recycles some of the vocabulary students have looked at – because the starting point for the vocabulary list was the language from the conversation. Again, the principle here is that students get repeated exposure to language in different contexts. (Note that the examples in the conversation are a bit different to those in the vocab task). By definition, this principle implies that any item of language is only partially learned when it is first ‘taught’.

Listening materials also allow for a focus on sound shapes in the language. There are limits to how far materials can ensure students get this focus, because the process of the listening has to be mediated by the teacher’s use of the listening material. In brief, I often will play the listening – or sections of it – multiple times, and may draw attention to what might be an unexpected sound shape for students, which may have caused a misunderstanding. This process is one for a different post.

Again, speaking follows the listening here and students exchange thoughts and ideas related to the listening content.

3 Listening

The coursebook sequence now moves on to a listening task. In this particular case, the listening is a kind of model for a conversation the students will do at the end of the lesson (and that we think they might hear or take part in outside the class). As I mentioned before, while it does contain items of the grammar, it is the conversation and its naturalness that is the starting point, with the grammar being selected afterwards. I think the conversation here does sound natural (in the way a drama script might) despite the fact that it isn’t actually authentic speech with all its pauses and overlaps and fillers, etc. I hope to discuss this more in a post on materials banks at a later date.

The listening also recycles some of the vocabulary students have looked at – because the starting point for the vocabulary list was the language from the conversation. Again, the principle here is that students get repeated exposure to language in different contexts. (Note that the examples in the conversation are a bit different to those in the vocab task). By definition, this principle implies that any item of language is only partially learned when it is first ‘taught’.

Listening materials also allow for a focus on sound shapes in the language. There are limits to how far materials can ensure students get this focus, because the process of the listening has to be mediated by the teacher’s use of the listening material. In brief, I often will play the listening – or sections of it – multiple times, and may draw attention to what might be an unexpected sound shape for students, which may have caused a misunderstanding. This process is one for a different post.

Again, speaking follows the listening here and students exchange thoughts and ideas related to the listening content.

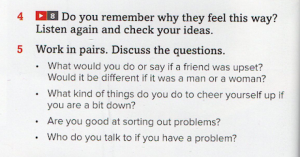

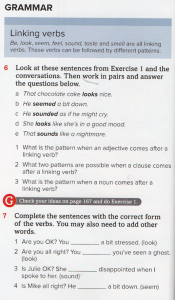

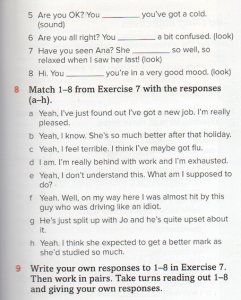

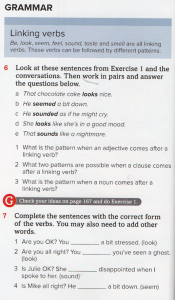

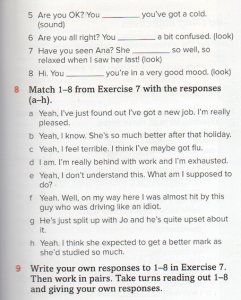

4 Grammar

Which brings us on to the grammar – in this case, ‘linking verbs’ (a.k.a. copula verbs). If this language has come up previously as part of students’ output, I might make use of those examples to remind students of the corrections we looked at and briefly elicit / discuss why their original utterances were wrong. I might ask them to look at the grammar box and discuss the questions, or just move straight on to the exercise. The latter would be my usual option, as some students may already know this language while the exercise allows me to find out who knows what.

The examples in the exercise all follow a similar pattern which is quite common in spoken English and would be a good starting point for a conversation on feelings (e.g. Are you OK? You look a bit stressed.). I also assume that students probably already know how to say ‘Are you OK?’ and may even have the capacity to follow this up with some form of ‘you look’. Whether all the students in the class are ‘ready’ to learn this, I can’t know, but some might be. For the rest, I assume that following on from studying it, they may notice this pattern the next time they hear it or be more likely to attempt it the next time they have opportunity to do so. That’s how I believe their acquisition of language over time is speeded up.

From a lexical approach point of view, it’s also important to have examples or contexts which are realistic, because a lexical view of language would suggest that students could learn some of these questions as lexis / fixed chunks of language that could then be used whole. Of course, this learning of the whole phrase may not be immediately successful and may depend on repeated encounters!

When going through the answers, I’d usually ask questions like why the correct response is ‘look’ rather than ‘look like’ and so on. I think this encourages noticing. I may also ask about other language in the exercise. For instance, I might say: ‘What’s the opposite of disappointed?’ or ‘What might you ask if you are confused by something?’

The second part of the ‘grammar’ is really a vocabulary exercise, exploring replies and co-text which could be associated with the adjectives. In fact, this is again an opportunity to re-encounter vocabulary that was previously ‘taught’. I sometimes ask students to do these tasks in pairs. It is a kind of problem solving task and they sometimes discuss the meaning of any words that one or other of them doesn’t know. Is that different to problem solving tasks in Task-Based Learning? Is talking about language not somehow doing things with English? Is it not at all authentic? It is, of course, possible to do too much of this kind of thing in class, but it certainly shouldn’t be dismissed altogether.

Going through the answers here, I’d again sometimes ask questions about new language. For example, ‘Why do couples typically split up?’ and ‘How might people get behind at work? What might be the consequence?’ I sometimes draw attention to patterns such as I didn’t expect it to be so … . I normally ask students to offer alternatives to end a sentence starter such as: I didn’t expect London to be so … Students sometimes will add a noun and I’ll point out it would then need to be ‘such a + noun’. Sometimes the responses to these questions are surprising, sometimes they lead to a genuine discussion among the class which I encourage or might formally instigate if students seem interested. I might, for instance, ask ‘Have you heard of any couples splitting up recently? What happened?’ At other times, I’ll just move on to the next ‘practice’ task.

I get students to read out the conversations and try to continue them. Then I often get them to write their own versions and practise them. Are these tasks meaning focused? Are they authentic? Well, kind of, because students have to process meaning to continue the conversations in realistic ways. And what often happens is that students will try to make the kinds of responses that are focused on in the next task. Sometimes they may say them correctly as they know them already, sometimes they will produce something similar, but not correct. I may then use these examples in feedback as a way to introduce the next task.

4 Grammar

Which brings us on to the grammar – in this case, ‘linking verbs’ (a.k.a. copula verbs). If this language has come up previously as part of students’ output, I might make use of those examples to remind students of the corrections we looked at and briefly elicit / discuss why their original utterances were wrong. I might ask them to look at the grammar box and discuss the questions, or just move straight on to the exercise. The latter would be my usual option, as some students may already know this language while the exercise allows me to find out who knows what.

The examples in the exercise all follow a similar pattern which is quite common in spoken English and would be a good starting point for a conversation on feelings (e.g. Are you OK? You look a bit stressed.). I also assume that students probably already know how to say ‘Are you OK?’ and may even have the capacity to follow this up with some form of ‘you look’. Whether all the students in the class are ‘ready’ to learn this, I can’t know, but some might be. For the rest, I assume that following on from studying it, they may notice this pattern the next time they hear it or be more likely to attempt it the next time they have opportunity to do so. That’s how I believe their acquisition of language over time is speeded up.

From a lexical approach point of view, it’s also important to have examples or contexts which are realistic, because a lexical view of language would suggest that students could learn some of these questions as lexis / fixed chunks of language that could then be used whole. Of course, this learning of the whole phrase may not be immediately successful and may depend on repeated encounters!

When going through the answers, I’d usually ask questions like why the correct response is ‘look’ rather than ‘look like’ and so on. I think this encourages noticing. I may also ask about other language in the exercise. For instance, I might say: ‘What’s the opposite of disappointed?’ or ‘What might you ask if you are confused by something?’

The second part of the ‘grammar’ is really a vocabulary exercise, exploring replies and co-text which could be associated with the adjectives. In fact, this is again an opportunity to re-encounter vocabulary that was previously ‘taught’. I sometimes ask students to do these tasks in pairs. It is a kind of problem solving task and they sometimes discuss the meaning of any words that one or other of them doesn’t know. Is that different to problem solving tasks in Task-Based Learning? Is talking about language not somehow doing things with English? Is it not at all authentic? It is, of course, possible to do too much of this kind of thing in class, but it certainly shouldn’t be dismissed altogether.

Going through the answers here, I’d again sometimes ask questions about new language. For example, ‘Why do couples typically split up?’ and ‘How might people get behind at work? What might be the consequence?’ I sometimes draw attention to patterns such as I didn’t expect it to be so … . I normally ask students to offer alternatives to end a sentence starter such as: I didn’t expect London to be so … Students sometimes will add a noun and I’ll point out it would then need to be ‘such a + noun’. Sometimes the responses to these questions are surprising, sometimes they lead to a genuine discussion among the class which I encourage or might formally instigate if students seem interested. I might, for instance, ask ‘Have you heard of any couples splitting up recently? What happened?’ At other times, I’ll just move on to the next ‘practice’ task.

I get students to read out the conversations and try to continue them. Then I often get them to write their own versions and practise them. Are these tasks meaning focused? Are they authentic? Well, kind of, because students have to process meaning to continue the conversations in realistic ways. And what often happens is that students will try to make the kinds of responses that are focused on in the next task. Sometimes they may say them correctly as they know them already, sometimes they will produce something similar, but not correct. I may then use these examples in feedback as a way to introduce the next task.

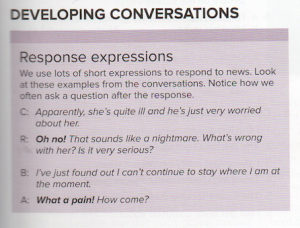

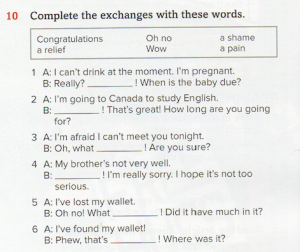

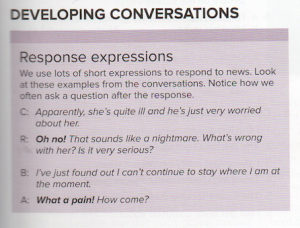

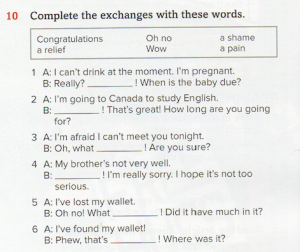

5 Developing conversations

This section of our Outcomes series generally aims to look at aspects of spoken language that don’t fit into traditional concepts of grammar or vocabulary, but at the same time are not purely ‘functional’. In this case, it’s response phrases such as Oh no! or Congratulations! but the exercise also looks at a feature of their use, which is that they are typically followed by questions. The task is a simple gap fill. You might just give the answers and then do the pronunciation task. Personally, as I go through the answers, I drill the phrases myself and I also ask students to suggest other responses/questions they might ask in each situation – cue the predictable (and often slightly tiresome!) jokes in response to being pregnant ‘Oh no! Who’s the father?’. It’s predictable, of course, because the conversations themselves are familiar and predictable. But again, responses may vary a bit. I remember one time a student suggested ‘Are you going to keep it?’ and there was a response from another student – ‘Oh, this is not possible!’ – and a discussion ensued about abortion. More often than not, though, students don’t say things like this or the discussion doesn’t develop. I don’t push this issue and go with whatever they suggest.

5 Developing conversations

This section of our Outcomes series generally aims to look at aspects of spoken language that don’t fit into traditional concepts of grammar or vocabulary, but at the same time are not purely ‘functional’. In this case, it’s response phrases such as Oh no! or Congratulations! but the exercise also looks at a feature of their use, which is that they are typically followed by questions. The task is a simple gap fill. You might just give the answers and then do the pronunciation task. Personally, as I go through the answers, I drill the phrases myself and I also ask students to suggest other responses/questions they might ask in each situation – cue the predictable (and often slightly tiresome!) jokes in response to being pregnant ‘Oh no! Who’s the father?’. It’s predictable, of course, because the conversations themselves are familiar and predictable. But again, responses may vary a bit. I remember one time a student suggested ‘Are you going to keep it?’ and there was a response from another student – ‘Oh, this is not possible!’ – and a discussion ensued about abortion. More often than not, though, students don’t say things like this or the discussion doesn’t develop. I don’t push this issue and go with whatever they suggest.

6 Pronunciation

The pronunciation task that follows is basically a drill. I personally don’t believe these tasks affect students’ pronunciation, particularly when it comes to intonation. For me, these tasks are always about students simply getting a feel for how language sounds, and playing with it in different ways. In the original edition, we asked students to practise the dialogues, but change the questions. This was seen by some teachers as too similar to the previous task so was cut in the second edition. I personally liked that repetition, but hey, each to their own.

6 Pronunciation

The pronunciation task that follows is basically a drill. I personally don’t believe these tasks affect students’ pronunciation, particularly when it comes to intonation. For me, these tasks are always about students simply getting a feel for how language sounds, and playing with it in different ways. In the original edition, we asked students to practise the dialogues, but change the questions. This was seen by some teachers as too similar to the previous task so was cut in the second edition. I personally liked that repetition, but hey, each to their own.

7 Conversation Practice

Finally, there is a conversation practice. This is an opportunity for students to re-use language that has been ‘taught’ over the previous sequence of tasks. In fact, we ask them to write the conversation, which allows them to do this more consciously, but in the end they are free to try and use whatever language they like. As with any task like this, as feedback, I will comment on errors or gaps in the knowledge based on what I hear. As before, sometimes these will be reminders of items students have encountered before, and sometimes they will be items that will be revisited later in the course, sometimes they will be completely new and unprepared for from my perspective as a teacher, because language and conversation is ultimately unpredictable.

Sometimes I do this task at the beginning of the task sequence and then do it again now. Sometimes I set it again as homework and students act out their conversation the following lesson. I also often revisit these conversations as part of a review. Students also have a video of a similar conversation that they can watch at home. And because this is the kind of chat that can come up in class, I sometimes initiate similar conversations – and sometimes students do (though often they don’t, of course!).

Coursebooks, TBL, Dogme and SLA

So what is there to take from all of this in terms of the debate on coursebooks and in particular the criticism of coursebooks from proponents of Dogme, TBLT, etc.? I can’t speak for all writers, but Hugh and I certainly write with what might be called affordances or the potentiality of spontaneous conversation in mind. We also write with an approach to teaching and managing a class that aims to take advantage of such potential. There is certainly pre-planning of language that we think might reflect what students may try and say at any given level and tasks which enable that language to be explored and encountered repeatedly over time. This will include writing texts and tasks later in the course that revisit language explicitly or that allow the teacher to revisit it (see the Vocabulary task and its use of the past perfect above). It seems to me that much of what TBLT and Dogme aims to promote: authenticity, spontaneity, student-centredness, interaction, potential for mistakes and learning, implicit learning – and all are possible within the coursebook-based lesson described above. Where we seem to differ from TBLT and Dogme is firstly in this pre-planning and, secondly, in the idea that a language-focused exercise can be a task that facilitates these things. Oh, and it’s worth repeating (again!) that in doing an initially mechanical language-focused exercise, we are not making a series of assumptions about how languages are learned (though others might be!)

As I stated in an earlier post, I actually think many writers and users of coursebooks do have many principles in common with proponents of TBLT/Dogme. Some of the debate may come from a fundamental point of principle as to the role of explicit learning. Our view is that in terms of vocabulary (and, to a lesser extent, grammar) meanings, explicit learning has a crucial part to play but development of usage is a long term rocky process, largely done implicitly.

However, some of the division caused by those criticising coursebooks comes from only looking at the surface of what’s on the pages, and this may also be exacerbated because teachers don’t talk enough about what they actually do in class and why. By the same token, my questioning of TBLT/Dogme centres on how lessons actually work. I understand that a material-free classroom can work in principle, but I think we need to question the practice. What exactly are the tasks? How are those tasks chosen? Why are they chosen? Why is some emerging language followed up on when other language not? What is the focus on form, if it happens? Is it OK to use material then? It seems to me, for example, that in choosing a task, TBLT practitioners must have some ideas of level and potential language in mind before the class. And when they want to develop that language, they must have in mind a new level of complexity. I have heard of anti-coursebook teachers making use of models and materials banks. To me that seems a lot like pre-planning which is prone to raise the same issues as use of a coursebook. This is what we will look at in the next one of these posts.

Want to think more about your teaching? Take a summer course with us in London.

Find out more about our most recent series of coursebooks, Outcomes.

7 Conversation Practice

Finally, there is a conversation practice. This is an opportunity for students to re-use language that has been ‘taught’ over the previous sequence of tasks. In fact, we ask them to write the conversation, which allows them to do this more consciously, but in the end they are free to try and use whatever language they like. As with any task like this, as feedback, I will comment on errors or gaps in the knowledge based on what I hear. As before, sometimes these will be reminders of items students have encountered before, and sometimes they will be items that will be revisited later in the course, sometimes they will be completely new and unprepared for from my perspective as a teacher, because language and conversation is ultimately unpredictable.

Sometimes I do this task at the beginning of the task sequence and then do it again now. Sometimes I set it again as homework and students act out their conversation the following lesson. I also often revisit these conversations as part of a review. Students also have a video of a similar conversation that they can watch at home. And because this is the kind of chat that can come up in class, I sometimes initiate similar conversations – and sometimes students do (though often they don’t, of course!).

Coursebooks, TBL, Dogme and SLA

So what is there to take from all of this in terms of the debate on coursebooks and in particular the criticism of coursebooks from proponents of Dogme, TBLT, etc.? I can’t speak for all writers, but Hugh and I certainly write with what might be called affordances or the potentiality of spontaneous conversation in mind. We also write with an approach to teaching and managing a class that aims to take advantage of such potential. There is certainly pre-planning of language that we think might reflect what students may try and say at any given level and tasks which enable that language to be explored and encountered repeatedly over time. This will include writing texts and tasks later in the course that revisit language explicitly or that allow the teacher to revisit it (see the Vocabulary task and its use of the past perfect above). It seems to me that much of what TBLT and Dogme aims to promote: authenticity, spontaneity, student-centredness, interaction, potential for mistakes and learning, implicit learning – and all are possible within the coursebook-based lesson described above. Where we seem to differ from TBLT and Dogme is firstly in this pre-planning and, secondly, in the idea that a language-focused exercise can be a task that facilitates these things. Oh, and it’s worth repeating (again!) that in doing an initially mechanical language-focused exercise, we are not making a series of assumptions about how languages are learned (though others might be!)

As I stated in an earlier post, I actually think many writers and users of coursebooks do have many principles in common with proponents of TBLT/Dogme. Some of the debate may come from a fundamental point of principle as to the role of explicit learning. Our view is that in terms of vocabulary (and, to a lesser extent, grammar) meanings, explicit learning has a crucial part to play but development of usage is a long term rocky process, largely done implicitly.

However, some of the division caused by those criticising coursebooks comes from only looking at the surface of what’s on the pages, and this may also be exacerbated because teachers don’t talk enough about what they actually do in class and why. By the same token, my questioning of TBLT/Dogme centres on how lessons actually work. I understand that a material-free classroom can work in principle, but I think we need to question the practice. What exactly are the tasks? How are those tasks chosen? Why are they chosen? Why is some emerging language followed up on when other language not? What is the focus on form, if it happens? Is it OK to use material then? It seems to me, for example, that in choosing a task, TBLT practitioners must have some ideas of level and potential language in mind before the class. And when they want to develop that language, they must have in mind a new level of complexity. I have heard of anti-coursebook teachers making use of models and materials banks. To me that seems a lot like pre-planning which is prone to raise the same issues as use of a coursebook. This is what we will look at in the next one of these posts.

Want to think more about your teaching? Take a summer course with us in London.

Find out more about our most recent series of coursebooks, Outcomes.

1 Speaking

So at the start of this particular lesson, there’s a photo of a family at the end of a dinner. It’s a rather ambiguous scene that students discuss. During this discussion, students generally may well try to use copula verbs such as look and seem (which is the grammar point on the next page) and they might say things like ‘He looks like depressed’ or ‘He look too much’. There are choices to be made at this point. If students do make mistakes with the copula verbs, the teacher could choose to:

1 Speaking

So at the start of this particular lesson, there’s a photo of a family at the end of a dinner. It’s a rather ambiguous scene that students discuss. During this discussion, students generally may well try to use copula verbs such as look and seem (which is the grammar point on the next page) and they might say things like ‘He looks like depressed’ or ‘He look too much’. There are choices to be made at this point. If students do make mistakes with the copula verbs, the teacher could choose to:

- ignore the mistake

- correct the mistake and move directly to further practice/examples (using the coursebook or their own resources).

- draw attention to the mistake, but continue with the coursebook sequence.

2 Vocabulary (feelings)

The coursebook sequence of tasks now moves on to vocabulary. Usually, I would tell students they are going to learn more language about feelings and then set them the task to ‘guess’ (there are options given) the meaning of the words in bold from the context. The idea is to help develop students’ ability to guess unknown vocabulary in context (I’ll talk more about this in next post, by the way). While the focus of the material may be taken as the list of the adjectives in bold here, my aim as a teacher and writer is to look at language beyond these adjectives. I would expect students to know the meaning of some of the adjectives already, and maybe even all of them if they have studied them at home before the start of the unit, but of course this is different to being able to use the words in conversation or in a text.

When I am going through the answers to the first part, I usually ask questions akin to those in the next part of the vocabulary section (see below), and may also draw attention to chunks, patterns and grammar. For example, this is one example from the exercise:

We left at six in the morning and didn’t get back till midnight. I was exhausted.

From this, I might explore aspects of the pattern here by telling students about a night out. I might say – and maybe write on the board – I went out at 10 at night and didn’t get back home till 7 in the morning. I might then perhaps elicit ideas from students about exhausting days or journeys they have had using the pattern.

Another example is I was pleasantly surprised by the film. I didn’t expect it to be so good. Here, I might ask students about the opposite of pleasantly surprised (= disappointed) and give students prompts to complete such as: I was pleasantly surprised by the weather. I expected it … or I was a bit disappointed by the hotel. I …. .

I don’t assume this new language will necessarily be learned at this stage, but I believe that the noticing might help students pick up the pattern didn’t …. till / until …. or provoke errors with (and subsequent noticing of) patterns around the word expect. And in noticing this here, they may notice it when they read and talk outside the class, which, over time, may transfer to uptake.

I might also ask about grammar. For instance, I might ask ‘Why does it say she was furious about the mess they had made – why use the past perfect there?’ I can ask this here because we looked at past perfect in the previous unit, and so I know they probably haven’t mastered it then and need to revisit it (as they will do in various tasks that follow and over the rest of the course).

The second task for the vocabulary here is a number of ‘divergent’ concept checking questions of the type discussed in this post. They explore usage of the words (because words are not just about meaning). While this isn’t a natural conversation, it is a meaning-focused task in the way a quick crossword is and some of what students try to say in response to these questions will result in errors and opportunities for acquisition – though (at the risk of repeating myself) I do not assume that any language I subsequently correct / teach here will be acquired at that point.

At the end of the vocabulary section, I would normally add another task which is not in the book, where students talk about a time they experienced one or more of these feelings and / or I would ask them to talk about the photos along the top of the page. In fact, this task was originally there in the final draft of the book, but was cut due to lack of space on the page. I do this partly to give students the opportunity to practise (or proceduralise, if you prefer that term) some language they have learned, but I also accept that the choice of language is up to the students and they may use language other than that which has been ‘taught’. In giving feedback on this task, I do much the same as before. I notice some gaps in knowledge or where communication breakdowns have happened, and I try to help students overcome them. Some of that help may mean referring back to something which was ‘taught’ before, sometimes it will be something new.

Sometimes students try to say language which I know is included in a later exercise in the lesson or even in a later unit (as I have written and used the book, I often remember these things!), so I might make a particular point of teaching that language here (because I know students need repeated exposure to language in different contexts over time). I also try to keep some kind of record of language that has come up through tasks and has been highlighted so I can revise it another day or recycle it in my teacher talk. I might write it down or take a photo of the boardwork.

Presumably, as I can’t listen to all conversations at the same time, there will also be other moments where students have to get round difficulties they have, which may also lead to acquisition (or not!).

2 Vocabulary (feelings)

The coursebook sequence of tasks now moves on to vocabulary. Usually, I would tell students they are going to learn more language about feelings and then set them the task to ‘guess’ (there are options given) the meaning of the words in bold from the context. The idea is to help develop students’ ability to guess unknown vocabulary in context (I’ll talk more about this in next post, by the way). While the focus of the material may be taken as the list of the adjectives in bold here, my aim as a teacher and writer is to look at language beyond these adjectives. I would expect students to know the meaning of some of the adjectives already, and maybe even all of them if they have studied them at home before the start of the unit, but of course this is different to being able to use the words in conversation or in a text.

When I am going through the answers to the first part, I usually ask questions akin to those in the next part of the vocabulary section (see below), and may also draw attention to chunks, patterns and grammar. For example, this is one example from the exercise:

We left at six in the morning and didn’t get back till midnight. I was exhausted.

From this, I might explore aspects of the pattern here by telling students about a night out. I might say – and maybe write on the board – I went out at 10 at night and didn’t get back home till 7 in the morning. I might then perhaps elicit ideas from students about exhausting days or journeys they have had using the pattern.

Another example is I was pleasantly surprised by the film. I didn’t expect it to be so good. Here, I might ask students about the opposite of pleasantly surprised (= disappointed) and give students prompts to complete such as: I was pleasantly surprised by the weather. I expected it … or I was a bit disappointed by the hotel. I …. .

I don’t assume this new language will necessarily be learned at this stage, but I believe that the noticing might help students pick up the pattern didn’t …. till / until …. or provoke errors with (and subsequent noticing of) patterns around the word expect. And in noticing this here, they may notice it when they read and talk outside the class, which, over time, may transfer to uptake.

I might also ask about grammar. For instance, I might ask ‘Why does it say she was furious about the mess they had made – why use the past perfect there?’ I can ask this here because we looked at past perfect in the previous unit, and so I know they probably haven’t mastered it then and need to revisit it (as they will do in various tasks that follow and over the rest of the course).

The second task for the vocabulary here is a number of ‘divergent’ concept checking questions of the type discussed in this post. They explore usage of the words (because words are not just about meaning). While this isn’t a natural conversation, it is a meaning-focused task in the way a quick crossword is and some of what students try to say in response to these questions will result in errors and opportunities for acquisition – though (at the risk of repeating myself) I do not assume that any language I subsequently correct / teach here will be acquired at that point.

At the end of the vocabulary section, I would normally add another task which is not in the book, where students talk about a time they experienced one or more of these feelings and / or I would ask them to talk about the photos along the top of the page. In fact, this task was originally there in the final draft of the book, but was cut due to lack of space on the page. I do this partly to give students the opportunity to practise (or proceduralise, if you prefer that term) some language they have learned, but I also accept that the choice of language is up to the students and they may use language other than that which has been ‘taught’. In giving feedback on this task, I do much the same as before. I notice some gaps in knowledge or where communication breakdowns have happened, and I try to help students overcome them. Some of that help may mean referring back to something which was ‘taught’ before, sometimes it will be something new.

Sometimes students try to say language which I know is included in a later exercise in the lesson or even in a later unit (as I have written and used the book, I often remember these things!), so I might make a particular point of teaching that language here (because I know students need repeated exposure to language in different contexts over time). I also try to keep some kind of record of language that has come up through tasks and has been highlighted so I can revise it another day or recycle it in my teacher talk. I might write it down or take a photo of the boardwork.

Presumably, as I can’t listen to all conversations at the same time, there will also be other moments where students have to get round difficulties they have, which may also lead to acquisition (or not!).

3 Listening

The coursebook sequence now moves on to a listening task. In this particular case, the listening is a kind of model for a conversation the students will do at the end of the lesson (and that we think they might hear or take part in outside the class). As I mentioned before, while it does contain items of the grammar, it is the conversation and its naturalness that is the starting point, with the grammar being selected afterwards. I think the conversation here does sound natural (in the way a drama script might) despite the fact that it isn’t actually authentic speech with all its pauses and overlaps and fillers, etc. I hope to discuss this more in a post on materials banks at a later date.

The listening also recycles some of the vocabulary students have looked at – because the starting point for the vocabulary list was the language from the conversation. Again, the principle here is that students get repeated exposure to language in different contexts. (Note that the examples in the conversation are a bit different to those in the vocab task). By definition, this principle implies that any item of language is only partially learned when it is first ‘taught’.

Listening materials also allow for a focus on sound shapes in the language. There are limits to how far materials can ensure students get this focus, because the process of the listening has to be mediated by the teacher’s use of the listening material. In brief, I often will play the listening – or sections of it – multiple times, and may draw attention to what might be an unexpected sound shape for students, which may have caused a misunderstanding. This process is one for a different post.

Again, speaking follows the listening here and students exchange thoughts and ideas related to the listening content.

3 Listening

The coursebook sequence now moves on to a listening task. In this particular case, the listening is a kind of model for a conversation the students will do at the end of the lesson (and that we think they might hear or take part in outside the class). As I mentioned before, while it does contain items of the grammar, it is the conversation and its naturalness that is the starting point, with the grammar being selected afterwards. I think the conversation here does sound natural (in the way a drama script might) despite the fact that it isn’t actually authentic speech with all its pauses and overlaps and fillers, etc. I hope to discuss this more in a post on materials banks at a later date.

The listening also recycles some of the vocabulary students have looked at – because the starting point for the vocabulary list was the language from the conversation. Again, the principle here is that students get repeated exposure to language in different contexts. (Note that the examples in the conversation are a bit different to those in the vocab task). By definition, this principle implies that any item of language is only partially learned when it is first ‘taught’.

Listening materials also allow for a focus on sound shapes in the language. There are limits to how far materials can ensure students get this focus, because the process of the listening has to be mediated by the teacher’s use of the listening material. In brief, I often will play the listening – or sections of it – multiple times, and may draw attention to what might be an unexpected sound shape for students, which may have caused a misunderstanding. This process is one for a different post.

Again, speaking follows the listening here and students exchange thoughts and ideas related to the listening content.

- What would you do or say if a friend was upset? Would it be different if it was a man or a woman?

- What kind of things do you do to cheer yourself up if you are a bit down?

- Are you good at sorting out problems?

- Who do you talk to if you have a problem?

4 Grammar

Which brings us on to the grammar – in this case, ‘linking verbs’ (a.k.a. copula verbs). If this language has come up previously as part of students’ output, I might make use of those examples to remind students of the corrections we looked at and briefly elicit / discuss why their original utterances were wrong. I might ask them to look at the grammar box and discuss the questions, or just move straight on to the exercise. The latter would be my usual option, as some students may already know this language while the exercise allows me to find out who knows what.

The examples in the exercise all follow a similar pattern which is quite common in spoken English and would be a good starting point for a conversation on feelings (e.g. Are you OK? You look a bit stressed.). I also assume that students probably already know how to say ‘Are you OK?’ and may even have the capacity to follow this up with some form of ‘you look’. Whether all the students in the class are ‘ready’ to learn this, I can’t know, but some might be. For the rest, I assume that following on from studying it, they may notice this pattern the next time they hear it or be more likely to attempt it the next time they have opportunity to do so. That’s how I believe their acquisition of language over time is speeded up.

From a lexical approach point of view, it’s also important to have examples or contexts which are realistic, because a lexical view of language would suggest that students could learn some of these questions as lexis / fixed chunks of language that could then be used whole. Of course, this learning of the whole phrase may not be immediately successful and may depend on repeated encounters!

When going through the answers, I’d usually ask questions like why the correct response is ‘look’ rather than ‘look like’ and so on. I think this encourages noticing. I may also ask about other language in the exercise. For instance, I might say: ‘What’s the opposite of disappointed?’ or ‘What might you ask if you are confused by something?’

The second part of the ‘grammar’ is really a vocabulary exercise, exploring replies and co-text which could be associated with the adjectives. In fact, this is again an opportunity to re-encounter vocabulary that was previously ‘taught’. I sometimes ask students to do these tasks in pairs. It is a kind of problem solving task and they sometimes discuss the meaning of any words that one or other of them doesn’t know. Is that different to problem solving tasks in Task-Based Learning? Is talking about language not somehow doing things with English? Is it not at all authentic? It is, of course, possible to do too much of this kind of thing in class, but it certainly shouldn’t be dismissed altogether.

Going through the answers here, I’d again sometimes ask questions about new language. For example, ‘Why do couples typically split up?’ and ‘How might people get behind at work? What might be the consequence?’ I sometimes draw attention to patterns such as I didn’t expect it to be so … . I normally ask students to offer alternatives to end a sentence starter such as: I didn’t expect London to be so … Students sometimes will add a noun and I’ll point out it would then need to be ‘such a + noun’. Sometimes the responses to these questions are surprising, sometimes they lead to a genuine discussion among the class which I encourage or might formally instigate if students seem interested. I might, for instance, ask ‘Have you heard of any couples splitting up recently? What happened?’ At other times, I’ll just move on to the next ‘practice’ task.

I get students to read out the conversations and try to continue them. Then I often get them to write their own versions and practise them. Are these tasks meaning focused? Are they authentic? Well, kind of, because students have to process meaning to continue the conversations in realistic ways. And what often happens is that students will try to make the kinds of responses that are focused on in the next task. Sometimes they may say them correctly as they know them already, sometimes they will produce something similar, but not correct. I may then use these examples in feedback as a way to introduce the next task.

4 Grammar

Which brings us on to the grammar – in this case, ‘linking verbs’ (a.k.a. copula verbs). If this language has come up previously as part of students’ output, I might make use of those examples to remind students of the corrections we looked at and briefly elicit / discuss why their original utterances were wrong. I might ask them to look at the grammar box and discuss the questions, or just move straight on to the exercise. The latter would be my usual option, as some students may already know this language while the exercise allows me to find out who knows what.

The examples in the exercise all follow a similar pattern which is quite common in spoken English and would be a good starting point for a conversation on feelings (e.g. Are you OK? You look a bit stressed.). I also assume that students probably already know how to say ‘Are you OK?’ and may even have the capacity to follow this up with some form of ‘you look’. Whether all the students in the class are ‘ready’ to learn this, I can’t know, but some might be. For the rest, I assume that following on from studying it, they may notice this pattern the next time they hear it or be more likely to attempt it the next time they have opportunity to do so. That’s how I believe their acquisition of language over time is speeded up.

From a lexical approach point of view, it’s also important to have examples or contexts which are realistic, because a lexical view of language would suggest that students could learn some of these questions as lexis / fixed chunks of language that could then be used whole. Of course, this learning of the whole phrase may not be immediately successful and may depend on repeated encounters!

When going through the answers, I’d usually ask questions like why the correct response is ‘look’ rather than ‘look like’ and so on. I think this encourages noticing. I may also ask about other language in the exercise. For instance, I might say: ‘What’s the opposite of disappointed?’ or ‘What might you ask if you are confused by something?’

The second part of the ‘grammar’ is really a vocabulary exercise, exploring replies and co-text which could be associated with the adjectives. In fact, this is again an opportunity to re-encounter vocabulary that was previously ‘taught’. I sometimes ask students to do these tasks in pairs. It is a kind of problem solving task and they sometimes discuss the meaning of any words that one or other of them doesn’t know. Is that different to problem solving tasks in Task-Based Learning? Is talking about language not somehow doing things with English? Is it not at all authentic? It is, of course, possible to do too much of this kind of thing in class, but it certainly shouldn’t be dismissed altogether.

Going through the answers here, I’d again sometimes ask questions about new language. For example, ‘Why do couples typically split up?’ and ‘How might people get behind at work? What might be the consequence?’ I sometimes draw attention to patterns such as I didn’t expect it to be so … . I normally ask students to offer alternatives to end a sentence starter such as: I didn’t expect London to be so … Students sometimes will add a noun and I’ll point out it would then need to be ‘such a + noun’. Sometimes the responses to these questions are surprising, sometimes they lead to a genuine discussion among the class which I encourage or might formally instigate if students seem interested. I might, for instance, ask ‘Have you heard of any couples splitting up recently? What happened?’ At other times, I’ll just move on to the next ‘practice’ task.

I get students to read out the conversations and try to continue them. Then I often get them to write their own versions and practise them. Are these tasks meaning focused? Are they authentic? Well, kind of, because students have to process meaning to continue the conversations in realistic ways. And what often happens is that students will try to make the kinds of responses that are focused on in the next task. Sometimes they may say them correctly as they know them already, sometimes they will produce something similar, but not correct. I may then use these examples in feedback as a way to introduce the next task.

5 Developing conversations

This section of our Outcomes series generally aims to look at aspects of spoken language that don’t fit into traditional concepts of grammar or vocabulary, but at the same time are not purely ‘functional’. In this case, it’s response phrases such as Oh no! or Congratulations! but the exercise also looks at a feature of their use, which is that they are typically followed by questions. The task is a simple gap fill. You might just give the answers and then do the pronunciation task. Personally, as I go through the answers, I drill the phrases myself and I also ask students to suggest other responses/questions they might ask in each situation – cue the predictable (and often slightly tiresome!) jokes in response to being pregnant ‘Oh no! Who’s the father?’. It’s predictable, of course, because the conversations themselves are familiar and predictable. But again, responses may vary a bit. I remember one time a student suggested ‘Are you going to keep it?’ and there was a response from another student – ‘Oh, this is not possible!’ – and a discussion ensued about abortion. More often than not, though, students don’t say things like this or the discussion doesn’t develop. I don’t push this issue and go with whatever they suggest.

5 Developing conversations

This section of our Outcomes series generally aims to look at aspects of spoken language that don’t fit into traditional concepts of grammar or vocabulary, but at the same time are not purely ‘functional’. In this case, it’s response phrases such as Oh no! or Congratulations! but the exercise also looks at a feature of their use, which is that they are typically followed by questions. The task is a simple gap fill. You might just give the answers and then do the pronunciation task. Personally, as I go through the answers, I drill the phrases myself and I also ask students to suggest other responses/questions they might ask in each situation – cue the predictable (and often slightly tiresome!) jokes in response to being pregnant ‘Oh no! Who’s the father?’. It’s predictable, of course, because the conversations themselves are familiar and predictable. But again, responses may vary a bit. I remember one time a student suggested ‘Are you going to keep it?’ and there was a response from another student – ‘Oh, this is not possible!’ – and a discussion ensued about abortion. More often than not, though, students don’t say things like this or the discussion doesn’t develop. I don’t push this issue and go with whatever they suggest.

6 Pronunciation

The pronunciation task that follows is basically a drill. I personally don’t believe these tasks affect students’ pronunciation, particularly when it comes to intonation. For me, these tasks are always about students simply getting a feel for how language sounds, and playing with it in different ways. In the original edition, we asked students to practise the dialogues, but change the questions. This was seen by some teachers as too similar to the previous task so was cut in the second edition. I personally liked that repetition, but hey, each to their own.

6 Pronunciation

The pronunciation task that follows is basically a drill. I personally don’t believe these tasks affect students’ pronunciation, particularly when it comes to intonation. For me, these tasks are always about students simply getting a feel for how language sounds, and playing with it in different ways. In the original edition, we asked students to practise the dialogues, but change the questions. This was seen by some teachers as too similar to the previous task so was cut in the second edition. I personally liked that repetition, but hey, each to their own.

7 Conversation Practice

Finally, there is a conversation practice. This is an opportunity for students to re-use language that has been ‘taught’ over the previous sequence of tasks. In fact, we ask them to write the conversation, which allows them to do this more consciously, but in the end they are free to try and use whatever language they like. As with any task like this, as feedback, I will comment on errors or gaps in the knowledge based on what I hear. As before, sometimes these will be reminders of items students have encountered before, and sometimes they will be items that will be revisited later in the course, sometimes they will be completely new and unprepared for from my perspective as a teacher, because language and conversation is ultimately unpredictable.

Sometimes I do this task at the beginning of the task sequence and then do it again now. Sometimes I set it again as homework and students act out their conversation the following lesson. I also often revisit these conversations as part of a review. Students also have a video of a similar conversation that they can watch at home. And because this is the kind of chat that can come up in class, I sometimes initiate similar conversations – and sometimes students do (though often they don’t, of course!).

Coursebooks, TBL, Dogme and SLA

So what is there to take from all of this in terms of the debate on coursebooks and in particular the criticism of coursebooks from proponents of Dogme, TBLT, etc.? I can’t speak for all writers, but Hugh and I certainly write with what might be called affordances or the potentiality of spontaneous conversation in mind. We also write with an approach to teaching and managing a class that aims to take advantage of such potential. There is certainly pre-planning of language that we think might reflect what students may try and say at any given level and tasks which enable that language to be explored and encountered repeatedly over time. This will include writing texts and tasks later in the course that revisit language explicitly or that allow the teacher to revisit it (see the Vocabulary task and its use of the past perfect above). It seems to me that much of what TBLT and Dogme aims to promote: authenticity, spontaneity, student-centredness, interaction, potential for mistakes and learning, implicit learning – and all are possible within the coursebook-based lesson described above. Where we seem to differ from TBLT and Dogme is firstly in this pre-planning and, secondly, in the idea that a language-focused exercise can be a task that facilitates these things. Oh, and it’s worth repeating (again!) that in doing an initially mechanical language-focused exercise, we are not making a series of assumptions about how languages are learned (though others might be!)

As I stated in an earlier post, I actually think many writers and users of coursebooks do have many principles in common with proponents of TBLT/Dogme. Some of the debate may come from a fundamental point of principle as to the role of explicit learning. Our view is that in terms of vocabulary (and, to a lesser extent, grammar) meanings, explicit learning has a crucial part to play but development of usage is a long term rocky process, largely done implicitly.

However, some of the division caused by those criticising coursebooks comes from only looking at the surface of what’s on the pages, and this may also be exacerbated because teachers don’t talk enough about what they actually do in class and why. By the same token, my questioning of TBLT/Dogme centres on how lessons actually work. I understand that a material-free classroom can work in principle, but I think we need to question the practice. What exactly are the tasks? How are those tasks chosen? Why are they chosen? Why is some emerging language followed up on when other language not? What is the focus on form, if it happens? Is it OK to use material then? It seems to me, for example, that in choosing a task, TBLT practitioners must have some ideas of level and potential language in mind before the class. And when they want to develop that language, they must have in mind a new level of complexity. I have heard of anti-coursebook teachers making use of models and materials banks. To me that seems a lot like pre-planning which is prone to raise the same issues as use of a coursebook. This is what we will look at in the next one of these posts.

Want to think more about your teaching? Take a summer course with us in London.

Find out more about our most recent series of coursebooks, Outcomes.

7 Conversation Practice

Finally, there is a conversation practice. This is an opportunity for students to re-use language that has been ‘taught’ over the previous sequence of tasks. In fact, we ask them to write the conversation, which allows them to do this more consciously, but in the end they are free to try and use whatever language they like. As with any task like this, as feedback, I will comment on errors or gaps in the knowledge based on what I hear. As before, sometimes these will be reminders of items students have encountered before, and sometimes they will be items that will be revisited later in the course, sometimes they will be completely new and unprepared for from my perspective as a teacher, because language and conversation is ultimately unpredictable.

Sometimes I do this task at the beginning of the task sequence and then do it again now. Sometimes I set it again as homework and students act out their conversation the following lesson. I also often revisit these conversations as part of a review. Students also have a video of a similar conversation that they can watch at home. And because this is the kind of chat that can come up in class, I sometimes initiate similar conversations – and sometimes students do (though often they don’t, of course!).

Coursebooks, TBL, Dogme and SLA

So what is there to take from all of this in terms of the debate on coursebooks and in particular the criticism of coursebooks from proponents of Dogme, TBLT, etc.? I can’t speak for all writers, but Hugh and I certainly write with what might be called affordances or the potentiality of spontaneous conversation in mind. We also write with an approach to teaching and managing a class that aims to take advantage of such potential. There is certainly pre-planning of language that we think might reflect what students may try and say at any given level and tasks which enable that language to be explored and encountered repeatedly over time. This will include writing texts and tasks later in the course that revisit language explicitly or that allow the teacher to revisit it (see the Vocabulary task and its use of the past perfect above). It seems to me that much of what TBLT and Dogme aims to promote: authenticity, spontaneity, student-centredness, interaction, potential for mistakes and learning, implicit learning – and all are possible within the coursebook-based lesson described above. Where we seem to differ from TBLT and Dogme is firstly in this pre-planning and, secondly, in the idea that a language-focused exercise can be a task that facilitates these things. Oh, and it’s worth repeating (again!) that in doing an initially mechanical language-focused exercise, we are not making a series of assumptions about how languages are learned (though others might be!)

As I stated in an earlier post, I actually think many writers and users of coursebooks do have many principles in common with proponents of TBLT/Dogme. Some of the debate may come from a fundamental point of principle as to the role of explicit learning. Our view is that in terms of vocabulary (and, to a lesser extent, grammar) meanings, explicit learning has a crucial part to play but development of usage is a long term rocky process, largely done implicitly.

However, some of the division caused by those criticising coursebooks comes from only looking at the surface of what’s on the pages, and this may also be exacerbated because teachers don’t talk enough about what they actually do in class and why. By the same token, my questioning of TBLT/Dogme centres on how lessons actually work. I understand that a material-free classroom can work in principle, but I think we need to question the practice. What exactly are the tasks? How are those tasks chosen? Why are they chosen? Why is some emerging language followed up on when other language not? What is the focus on form, if it happens? Is it OK to use material then? It seems to me, for example, that in choosing a task, TBLT practitioners must have some ideas of level and potential language in mind before the class. And when they want to develop that language, they must have in mind a new level of complexity. I have heard of anti-coursebook teachers making use of models and materials banks. To me that seems a lot like pre-planning which is prone to raise the same issues as use of a coursebook. This is what we will look at in the next one of these posts.

Want to think more about your teaching? Take a summer course with us in London.

Find out more about our most recent series of coursebooks, Outcomes.

I find this very interesting Hugh. I think TBLT is too complex and we are all still trying to figure out how to do it! Let’s be honest, teachers like course books as you just pick them up and get on with it. Why not a topic based syllabus with no mention of grammar until it is obvious that they need some help with it? Your course book, great as it is, is still a grammar-based syllabus albeit a lighter version. Project based learning is also another alternative. We seem to be doing what’s easy and that’s all. I do find it shocking that we still use course books in 2017.

Thanks for commenting Stephen. I (Andrew) actually wrote this particular post. Thanks for the compliment about Outcomes and you are right that it is a compromise and there is a very visible grammar syllabus. However, it is also a genuine topic based syllabus in that vocab speaking tasks, texts and even grammar (most of the time if not always) provide opportunities to explore topics and have genuine communication. You could, I think, drop the grammar sections altogether or use them as they come up in class as a kind of materials bank. That’s up to the teacher. I think project based lessons could also be excellent but may equally be less successful. Let’s share what you (or whoever) have done and what language was taught/acquired how it was recycled etc. My main issue here would be that I don’t see what I describe here – and what lots of teachers do with course books as easy. IOk planning projects is an extra skill and may be difficult, but it also takes thought and effort to manage conversation, notice gaps in knowledge, , help students notice, recycle language etc.

Thanks Andrew and sorry for calling you Hugh!

He’s been called worse things in his time.

🙂

That’s OK. Hadn’t taken any offence!

[…] is a response to a post by Andrew Walkley of Lexical Lab on his about how teachers can use coursebooks in a principled […]

I wrote a blog post because my comment would be too long. Thanks for giving such a detailed rationale. My post is https://freelanceteacherselfdevelopment.wordpress.com/2017/10/29/dogme-tblt-what-do-you-do-in-the-classroom/

Thanks. I will check it out.

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for this interesting account of one way through a unit from your coursebook. You give every indication of being an experienced, thoughtful, teacher and I’m sure your students appreciate you. When we get down to this level of detailed pedagogic procedures, all the particularities of context will play a part in deciding what you do and the learning outcomes, as you repeatedly recognise. .

Our disagreement centres on the key issue of synthetic versus analytical syllabuses. You choose to use a synthetic syllabus, where you decide what bits of language are to be taught, and where most of the time is spent teaching students explicit knowledge about the language: grammar, lexis – lexico-gammar if you like – and pronunciation. I choose to use an analytical syllabus where the learners decide what is to be taught through needs analysis to determine target tasks, and where most of the time is spent on scaffolding students’ engagement in pedogic tasks aimed at helping them to develop the implicit knowledge recquired to carry out the identified tasks.

I’ve consistently argued that your way of doing things flies in the face of robust findings from studies of SLA. The synthetic syllabus assumes that explicit instruction plus practice leads to implicit knowledge, but no such simple conversion occurs. While explicit knowledge helps, and while occasionally it helps to shift attention to explicit learning, language learning is fundamentally a matter of unconsciously learning when one’s attention is on meaning. The most telling aspect of the approach that you and Hugh Dellar promote is your view of language learning, explained in your “6 principles of how people learn languages”. I quote:

“Essentially, to learn any given item of language, people need to carry out the following stages:

• Understand the meaning of the item.

• Hear/see an example of the item in context.

• Approximate the sounds of the item.

• Pay attention to the item and notice its features.

• Do something with the item – use it in some way.

• Repeat these steps over time, when encountering the item again in other contexts.”

Leaving aside the adequacy or otherwise of this mechanistic “explanation”, what stands out is the importance given to stage 1: Understand the meaning of the item. Dellar is particularly dissmissive, always giving the impression that teachers should get on to the next stages ASAP, and recommending that translation as the easiest, most efficient way of dealing with meaning. What Dellar wants to do to the point of obsession is to teach words, and what both of you seem to fail to appreciate is the primary importance of giving students opportunities for implicit learning by concentrating on meaning, on communicating in the L2 for real, meaningful purposes. Meaningful communication about things students want to talk about, the negotiation of meaning, finding their voice, expressing themselves, working out the illocutionary force of messages, catching nuances, compensating for inadequate resources, and all the sorts of things involved in implicit language learning should, in my opinion be what goes on most of the time in class, not something given a ten minute slot here and there. Your plan for how to work through the sample unit seems preoccupied with teaching stuff, and I think it’s telling that right at the end you say: “Finally, there is a conversation practice”. Finally! But even here, you’re on top of them: “This is an opportunity for students to re-use language that has been ‘taught’ over the previous sequence of tasks. In fact, we ask them to write the conversation, which allows them to do this more consciously”.

Language leaning is not, I suggest, what you assume it to be. Meaning is crucial, implicit learning is the default mode, and all the thousands of “items” that you set out to teach are so inextricably inter-related as to be impossible to treat as exemplars in the way you recommend.